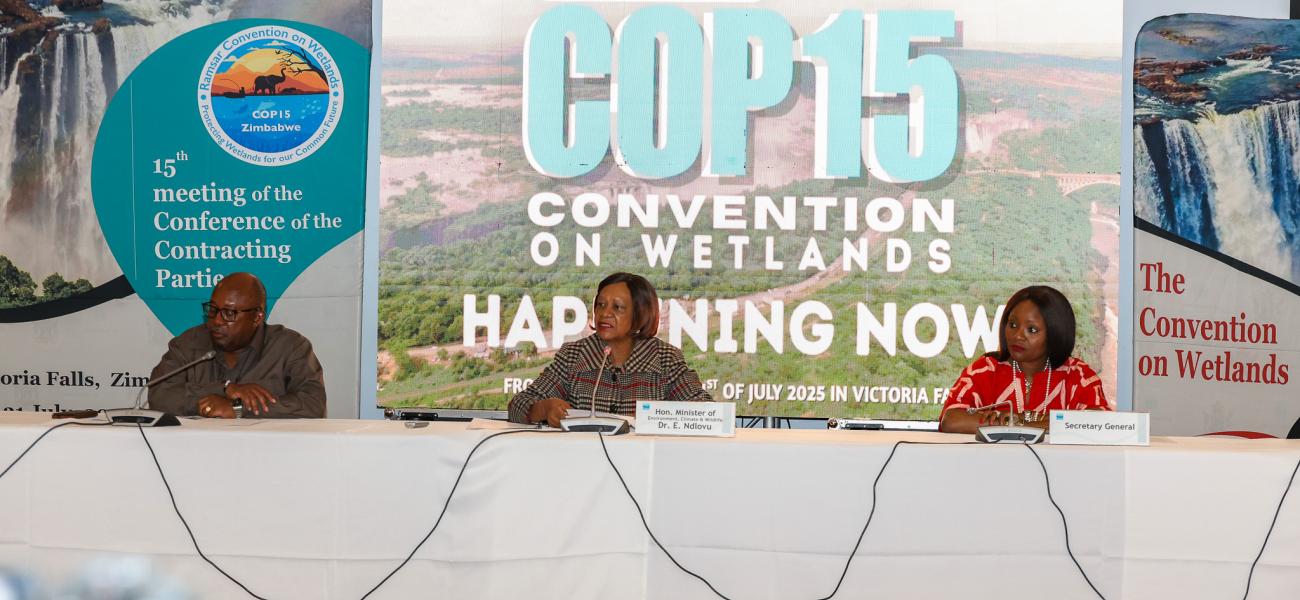

There is more to Victoria Falls than meets the eye. As the world’s largest waterfall, it marks the edge of a broader wetland system—one that supports water security, biodiversity, and livelihoods across southern Africa. As Zimbabwe hosts the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands (COP15), this location invites a closer look at the role wetlands play in sustaining life, and the decisions now needed to ensure they continue to do so.

COP15 arrives at a moment when wetlands—essential for climate resilience, food production, water supply, and biodiversity—are being lost and degraded at a rate that outpaces our responses. According to the Convention’s recently released flagship publication, the Global Wetland Outlook 2025, global wetland extent has declined by 22% since 1970, with losses continuing at an average rate of 0.52% per year. Degradation is accelerating: one in four remaining wetlands is now in poor ecological condition, with that proportion rising.

Despite these figures, wetlands still provide some of the most valuable and cost-effective solutions to the world’s most pressing challenges. They support water security for billions of people, absorb carbon more efficiently than most other ecosystems, and deliver an estimated $7.98 to $39.01 trillion in annual ecosystem services. Yet these contributions remain undervalued in decision-making and underfunded in public and private investment.

Zimbabwe knows better than many others just how important wetlands are. Wetlands provide water to more than two-thirds of the population, allowing for agriculture and tourism while buffering against floods and droughts. In response to growing pressures, the Government has implemented stronger legal protections, advanced local restoration initiatives, and deepened public engagement on wetland issues. The recent recognition of Victoria Falls as a Wetland City reflects both local commitment and the kind of urban ecological leadership that can be replicated elsewhere.

But national ambition—however strong—cannot substitute for global coordination. Wetlands are shared systems. They cross borders and connect sectors. Protecting them requires cooperation, consistent investment, and a shift in how they are understood: as strategic infrastructure that protects the stability of our economies, health systems, and food supply.

The Global Wetland Outlook 2025, sets out the scale of action needed: at least 123 million hectares must be restored to account for past loss, and 428 million hectares of remaining wetlands must be conserved. Doing so will require a major increase in global financing—somewhere between $275 and $550 billion per year—yet current investments fall far below that range. In fact, biodiversity conservation across all ecosystems receives just 0.25% of global GDP.

Zimbabwe’s hosting of COP15 is both timely and significant. It brings global attention to a region where wetlands are still deeply embedded in the landscape and culture, but also increasingly vulnerable. The conference presents a unique opportunity to prioritise wetlands in the biodiversity and climate agendas, and to align technical, political, and financial systems behind that goal.

Africa, home to approximately 40% of the world’s remaining wetlands, is well positioned to lead this shift. Many of the continent’s wetlands remain ecologically functional, and traditional knowledge of sustainable management practices endures. But external pressures—driven by extractive industries, land-use change, and climate stress—are growing rapidly. Without targeted support, we risk losing these ecosystems for good.

COP15 can help turn that tide. The Convention provides a platform for negotiation, as well as strategies, data, policies, and innovations. It is also a place to elevate voices that are often underrepresented—local communities, Indigenous groups, cities, and young people—who are already shaping the future of wetland stewardship on the ground.

This meeting in Victoria Falls will not solve every problem. But it can set a new trajectory. Decisions made here have the potential to ripple outward, shaping how wetlands are valued and governed across continents.

Rivers rarely follow straight lines, and neither does meaningful change. But when enough tributaries converge, that momentum can become difficult to ignore. It’s a life lesson that wetlands have taught us, and perhaps now the world is finally ready to listen.